Fatigue as a symptom of burnout

Anxiety and an over-adrenalized ‘wired but tired’ state are very common, especially in our increasingly blue-lit world of technology and perpetual doing-ness

A combination of various factors such as persistent sleep disturbance, living under chronic and sustained stress and having chicken pox as an adult, all meant that one day when I was at work for Hilton Hotels (where I was employed as a Health and Safety Manager two days a week) I was suddenly utterly incapacitated by severe pain. On another occasion, I recall standing at the bottom of the stairs, unable to go up them as my whole body felt like lead.

I went to my GP who, after a series of blood tests to eliminate the other usual culprits for such symptoms (such as iron deficiency or depression) diagnosed Chronic Fatigue Syndrome and signed me off work for a few months. I ended up being off for a whole year. After an Occupational Health assessment during which it was evident that I would not be able to return even part time, the company ended my contract.

I remained out of work for 13 years.

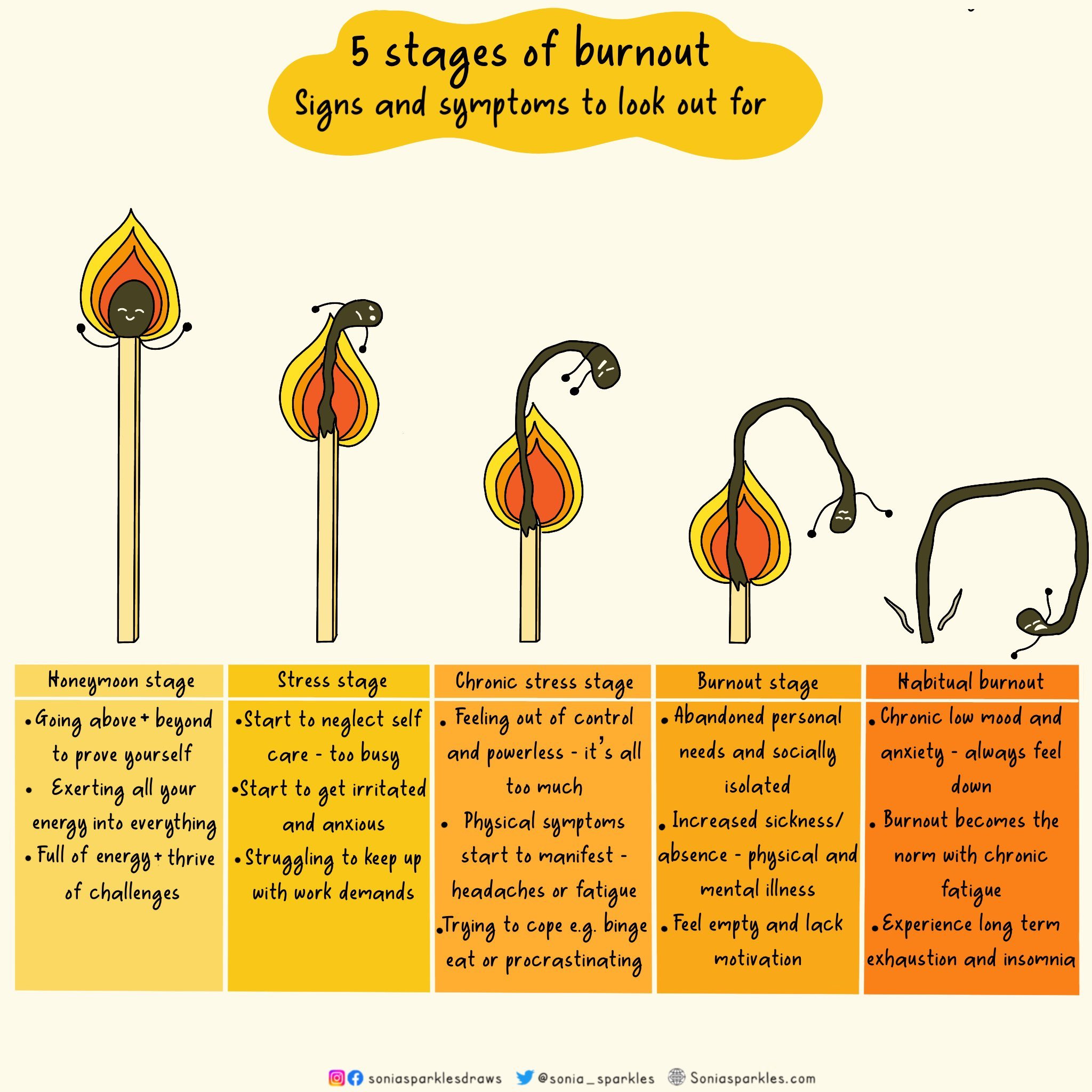

Although my living circumstances meant that thankfully I could initially take the hit financially, this had a considerable impact on my mental health and self-esteem. It also gave me a keen sense of the risks of burnout with some of the symptoms indicated in the chart above. Even though the start of the pandemic is now some years ago, we are all continuing to live under considerable stressors, it seems that things have continued to be pretty unrelenting in term of uncertainty with the war in the Ukraine and the pressures of the cost of living crisis. So understandably, our resources as human beings to sustain extended periods of additional stress are being somewhat stretched. These pressures can lead to all sorts of physical and psychological difficulties which then can have a negative impact on our performance at work or even with our capacity to sustain work.

What should individuals watch out for?

In conjunction with the chart above I would suggest that employees should be alerted to the warning signs, which include:

Persistent pain

Increased use of pain relief

Spinning too many plates at the same time

Gut issues

Sleep problems, debilitating fatigue

Shame, guilt, secrecy & denial

Feeling tired and wired

Endless ‘to-doing’

Desire to ‘stop the planet, I want to get off’

Frequently getting emotionally overwhelmed

Increased irritability/mood dysregulation- impacting relationships

What should employers watch out for?

A Gallup report from 2018 found that employees with enough time to do their work and who felt supported by their line managers were 70% less likely to suffer high burnout. It found the following main causes of burnout:

Unreasonable time pressure

Lack of communication & support from managers

Lack of role clarity

Unmanageable workload

Unfair treatment at work

How do individuals prevent burnout & fatigue?

We all have three emotional regulation systems: threat; drive; and soothing, says Emily Tims, my Specialist Physiotherapist colleague. “Although we need them all, we also need to be able to recognise when we’re spending too long in one of them. With burnout, we get stuck in either the threat or drive system.”

The following are required to help activate the soothing system:

Ensure good sleep habits: have a wind-down routine before bed; dark room; no evening caffeine, alcohol or exercise; minimise technology in the evening; minimise naps and lie-ins.

Balance rest and activity: identify your triggers, such as pushing ahead with work when you might be too tired, and set yourself ground rules; implement new routines that include effective rest, such as a 5-minute break every hour; ensure time for something completely different to work – anything from meditation and relaxation to listening to music or going for a walk.

Include physical activity: boosts mood; improves sleep, concentration, wellbeing, immune system, disease risk. Make a plan to ensure it’s easy to fit into life and keep it consistent. UK physical activity guidelines were revised by the Department of Health and Social Care in 2022 and as well as the usual 150 minutes a week of moderate-intensity exercise, there’s now more emphasis on strength training as part of the weekly routine, along with breaking up periods of inactivity.

How do employers prevent burnout & fatigue?

Employers have statutory obligations under the Health & Safety at Work Act (1974) – a duty of care for employee wellbeing, including mental health. This involves: minimising risk such as workload, role and expectations; identifying issues by monitoring absenteeism and presenteeism, also using the HSE risk assessment tool and management standards indicator tool.

Where areas of risk are identified, preventative strategies can be put in place by embedding a culture of wellbeing. This should include a focus on the following:

Achievable workload/targets.

Managing performance and ensuring a culture of disclosure so any problems are identified and adjustments can be made

Managers leading by example – right now, this could include not muting the children while they are on video calls and making it clear when they are and are not available

Managers given appropriate support and training

Encourage employees to take breaks away from the desk

Factor in physical activity – such as lunchtime walks

Encourage employees to switch off outside of work – make it clear to people when they are and are not expected to reply to emails

Implement flexible working

The risks of home working

Whilst being able to work from home is often a beneficial solution when someone maybe struggling with pain or fatigue, it can also lead to issues with presenteeism. Research findings commissioned by LinkedIn in partnership with the Mental Health Foundation, found that three in five (58%) HR leaders think long-term homeworking may have unearthed a culture of ‘e-presenteeism’, whereby workers feel obliged to be online as much as possible, even outside of work hours, and when they are feeling unwell.

The survey as a whole, which also included employee respondents, showed that individuals are working an average of 28 hours a month more since being required to work from home due to lockdown. It should be noted that the survey was taken early on and at the height of the uncertainty due to Covid-19. This is partly because boundaries can be blurred around when an employee is officially ‘at work’ or not especially given the ease and temptation of being notified of emails via our technology. As an employer, it is good practice to establish expectations around these areas with an employee who works from home to support understanding and communication and to protect the employees health.

Written by Katherine Sewell, Business Support Manager