What is Burnout?

At our recent team day I invited the team to discuss burnout and consider what we already do or could do more to help. Over the last 12 months I have come across so much about burnout, on social media, in the press, in professional publications and in general conversation. It is affecting people from all areas of life, from nurses in NHS roles to top corporate executives.

So is the incidence of burnout increasing or are we just talking about it more?

Earlier this year the TUC released a poll conducted by Thinks Insight about the increased risk of burnout due to more demanding work days. They report that people are facing more intense working days than ever, with less time for their private lives and an increased risk of burnout. More than half of workers (55%) reported that work had become more intense and demanding, according to polling for the union body. The TUC’s work intensification study said the shift was in part due to technology, as well as a decline in workers’ autonomy over how they spend their time.

Three out of five working people (61%) said they felt exhausted at the end of the working day, polling of more than 2,000 working people in England and Wales found. Workers also reported that the situation was getting worse. More than a third of those polled said they were spending more time outside contracted hours reading, sending and answering emails than they did a year earlier, in 2021. Women were more likely than men to say they felt exhausted at the end of most working days (67% to 56%) and that work was getting more intense (58% to 53%), according to polling for the TUC by Thinks Insight.

Overall, one in three working people said they were spending more time outside contracted hours doing core work activities and 40% reported they were required do more work in the same amount of time. The TUC has argued that urgent action must be taken to prevent the nation becoming burned out. The TUC’s General Secretary, Paul Nowak said,

“It’s time to tackle ever-increasing work intensity. That means strengthening enforcement so that workers can effectively exercise their rights. It means introducing a right to disconnect to let workers properly switch off outside of working hours. And it means making sure workers and unions are properly consulted on the use of AI and surveillance tech, and ensuring they are protected from punishing ways of working.”

So what exactly is burnout?

“Burn-out” is included in the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-11) as an occupational phenomenon and is not classified as a medical condition.

Burn-out is defined in ICD-11 as follows:

“Burn-out is a syndrome conceptualised as resulting from chronic workplace stress that has not been successfully managed. It is characterised by three dimensions:

- feelings of energy depletion or exhaustion;

- increased mental distance from one’s job, or feelings of negativism or cynicism related to one's job; and

- reduced professional efficacy.

Burn-out refers specifically to phenomena in the occupational context and should not be applied to describe experiences in other areas of life.”

However, we have noticed that the term ‘burnout’ is used informally to refer to other non-work contexts, eg. caregiver burnout, parental burnout. Although these would not fulfil the definition of burn-out according to the International Classification of Diseases; there are many overlapping characteristics with occupational burnout. In reality my clients often present with a mixed picture, describing pressures at work and at home.

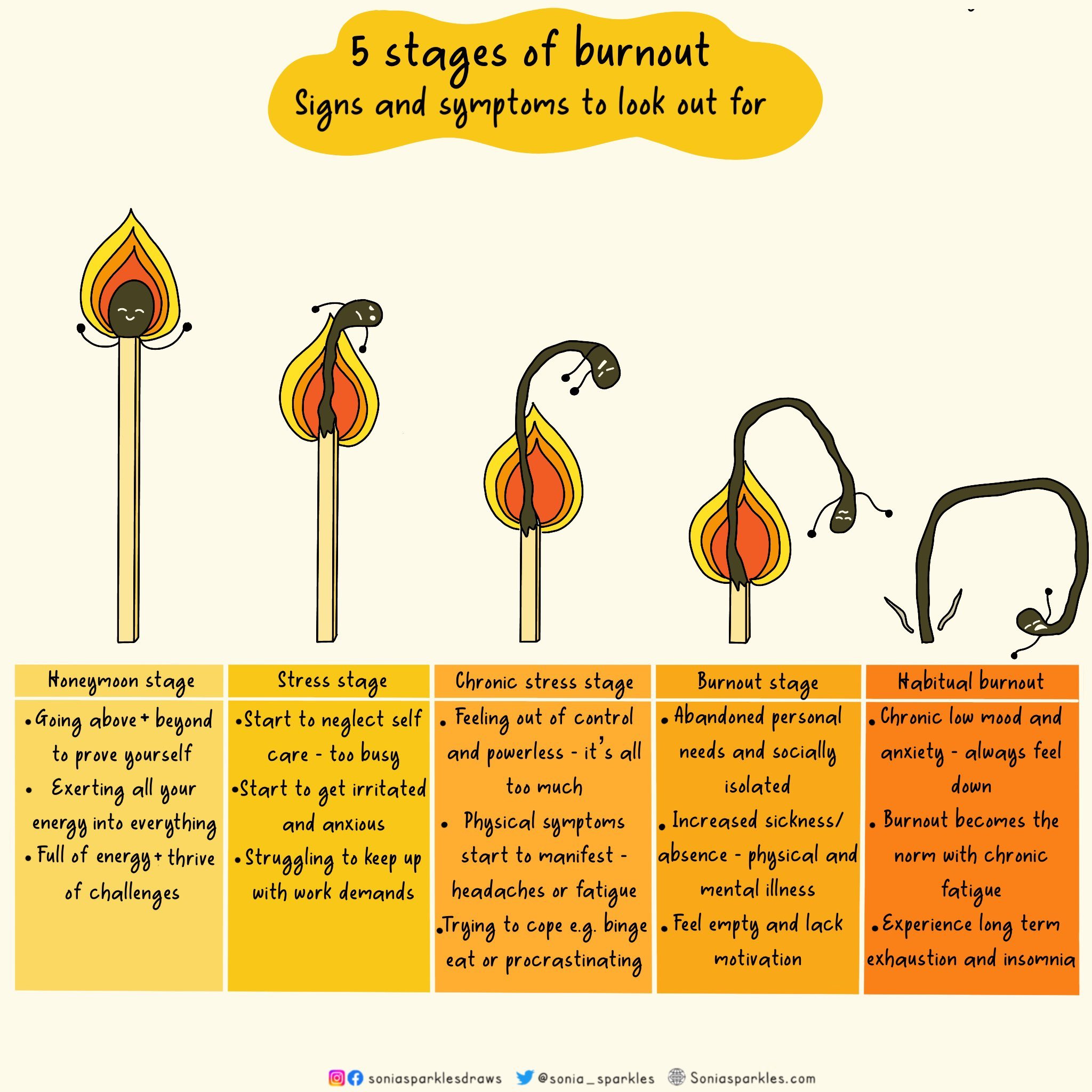

Reported symptoms can include headaches, aches and pain, sleep issues, fatigue, muscle tension, concentration difficulties, anxiety, low mood or emotional numbness, reduced productivity, lack of purpose or motivation, increased cynicism, feeling detached, and absenteeism. These symptoms are all frequently reported by our existing clients.

Why is burnout a concern?

Employee well-being:

Burnout negatively impacts physical and mental health, potentially leading to increased stress, anxiety and other long-term health issues. Dr Ananta Dave, the Royal College of Psychiatrists’ lead for wellbeing and retention, said: “Burnout is not considered a mental illness but can seriously impact mental health and lead to more prolonged mental health problems when not treated appropriately.”

Productivity and performance:

Burnout diminishes productivity, creativity and overall quality of work performed by an individual, which is likely, over time, to adversely impact the organisation’s performance and success.

Employee retention:

Burnout often contributes to higher staff attrition, with individual employees seeking better work environments. High levels of burnout can harm an organisation’s reputation, making it less attractive to potential employees and customers.

The main causes of burnout

Unmanageable workload and unreasonable time pressures

Not being treated well at work

Lack of communication and support

Lack of role clarity

Feeling unappreciated

What can we do about it?

The reality is that most change needs to come from employers in terms of management practices, company cultures and so on, but there are still things we can do to reduce the risk.

Balance of individual responsibility vs employer responsibility is a fraught area. However, employers have a statutory duty of care to their employees and need to do all they can to promote good mental health in the workplace and support those employees who become unwell.

Things that employers can address to reduce burnout are:

Measure through workplace questionnaires/surveys.

This stage is important both in assessing the current status but also reassessing after a period of intervention. Do the practices you have put in place actually make a difference?Eradicate toxic work behaviours - through looking at work culture, communication styles, management practices

Remember that even supportive work environments can have pockets of toxic behaviour.Create a supportive work environment

Strive for an open, trusting, transparent culture where employees feel valued and are fairy rewarded. Hire people who are a good fit and celebrate more compassionate leadershipPromote wellbeing/resilience training

Support adequate training and opportunities to put the skills learned into practice.

So what is resilience training?

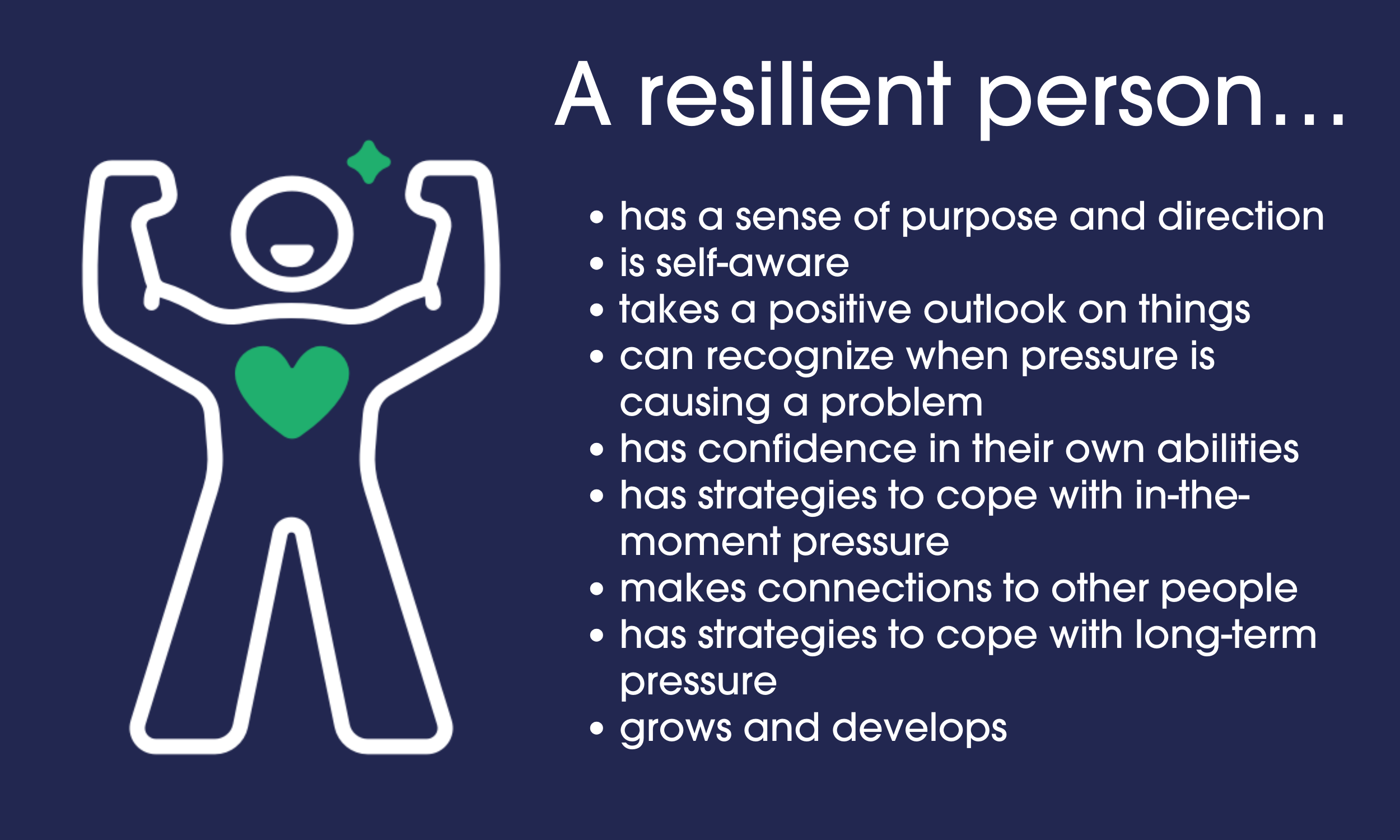

Resilience refers to the ability to bounce back or adapt positively in the face of challenges, adversity, or stressful situations. It involves coping with difficulties, overcoming obstacles, and maintaining mental fortitude and flexibility amidst hardships.

Can we train people to be more resilient?

The team, who are always interested in use of language and how this is perceived by individuals, had some interesting views on the word resilience. Our collective opinion was that we would prefer using the phrases ‘building overall wellbeing‘ or ‘building healthy habits at work’. Perhaps this is just semantics but our clinical experience informs us that words do matter.

Whatever the words we use we do believe that Individuals can reduce the risk of burnout by recognising and responding to signs of stress and building hepful skills and strategies

In our clinical experience, these practices are what many of our clients find helpful:

Establishing a work-life balance, making sure that pleasurable activities are not forgotten.

Prioritising self-care, so that nutrition and rest are included and taken seriously.

Regularly taking breaks which might include setting a reminder on your phone so that you remember to do so despite how absorbed you might get in a work task.

Setting achievable boundaries to separate work and personal life.

Maintaining a support network and remembering that it’s important to speak to others if you are struggling both in and outside work.

Dr Ananta Dave, the Royal College of Psychiatrists’ lead for wellbeing and retention, said

“People who are concerned about burnout should be able to seek help at work from their staff health and wellbeing service, line manager or occupational health team. Alternatively, they can talk to their GP about the support that is available”

Unfortunately, our experience at Vitality360 suggests that seeking help and getting support is not always easy. Over the years we have worked with people who are experiencing significant fatigue plus a range of associated symptoms which have resulted in significant absences from work. When we delve into their work history it is not uncommon to find that people were experiencing the warning signs of burnout long before they were unable to continue. When they are preparing to return to work we need to consider the impact of this on their health. If it is likely to have negative consequences we need to address this and contemplate what changes would need to occur to minimise the risk. We can definitely help people improve their own healthy work habits/personal wellbeing strategies which may make them more ‘resilient’ and I believe that if a person has developed these skills and does return to a toxic work culture they are more likely to cope in the short term but then have the confidence to leave in a planned way, securing a job in an organisation that is more supportive.

Our conclusion

Our conclusion, as a team, is that we can help at any stage of burnout. Our experience of working with people with persistent pain and fatigue is instantly transferable to working with those experiencing burnout. The main focus of our work is supporting people to optimally manage their health and wellbeing whilst participating in the activities that they most value. We support people in building awareness of things that influence their health positively and negatively. As individuals we all respond differently to activities and situations. What stresses one person out will energise another. Gradually, with our support, our clients increase their self awareness and develop a range of strategies that enable them to participate in a range of activities without exacerbating symptoms. The majority of our clients are of working age and sustaining work is a high priority. We can help identify the challenges each individual might encounter at work and find solutions. At times this is finding creative ways to bring their own self management skills/good health behaviours into the workplace. This could be as simple as finding somewhere quiet to rest at work, or feeling confident to stand and and stretch.

As you would predict, if our client works in a supportive environment these small changes are easy to make. However, our clients are often concerned about asking for adjustments at work, or behaving in a way that may appear a little different to their colleagues. So often I hear people say “that just won’t work in my office” or “my employer won’t be able to support that”. In these situations we can help in two ways. We can help individuals build confidence in communicating their needs at work, negotiating adjustments or increasing the understanding of their managers in why doing something differently would help. We can also communicate directly with employers, advocating for our clients and finding a mutually satisfactory way forward. In essence, we try to find a way that our clients can work well in a variety of environments, with a variety of employers. When everything is aligned, work is good for health.

I would argue that this personalised approach to health and wellbeing is more advantageous than funding a set resilience programme.

If you are an individual struggling at any stage of burnout consider asking for help. Ask your employer what they can do to help internally but it may also be worth asking if funding is available to access specialist support.

Written by Beverly Knops, Executive Manager & Specialist OT

References and Resources

Burn-out an "occupational phenomenon": International Classification of Diseases (who.int)

Beyond burnout: What helps—and what doesn’t | McKinsey

The Staff burn-out syndrome Freudenberger, H.J

NICE Guidance: Workplace Health Management Practices

Burnout statistics and guidance

HSE Management Standards Indicator Tool